FOIAengine: Requests Pointed to SBF’s Shaky World Long Before FTX Imploded

Jacob Silverman is a cryptocurrency savant and Jeopardy champion with 35,000 Twitter followers and stories to tell. A few years ago, the 38-year-old recalled his days as a “boomerang child” during the Great Recession. Despite being raised in privilege – “son of lawyers, private schools, no college debt” – he’d ended up moving back to his parents’ basement, “a linoleum warren of adolescent artifacts and piles of books that I ordered from eBay when stoned late at night.”

He also had “a childish infatuation with gadgets” and, it turns out, shiny objects. Which made Silverman perhaps just the person to get inside the head of another cryptocurrency savant with a dorm-room lifestyle: Sam Bankman-Fried.

The wild-haired founder of FTX, the mastermind behind what may be the greatest financial fraud in the history of mankind, became Silverman’s obsession.

And his quarry.

Silverman, an author and a contributing editor at the New Republic, has seen his journalistic career improve in the months following FTX’s implosion and Bankman-Fried’s arrest. Next week, he’s launching a new podcast, The Naked Emperor, that promises “a wild ride in search of an answer to the question: ‘How did Sam Bankman-Fried happen?'”

It’s a question that, in retrospect, might seem logical to ask — particularly given the explosion of litigation that resulted. Most recently, on March 2, the new managers at FTX told the Delaware bankruptcy court they had identified a deficit of $8.9 billion in customer funds that cannot be accounted for. Four days later, they filed suit in Delaware against crypto asset manager Grayscale Investments to claw back some of the billions. Grayscale, in turn, is suing the Securities and Exchange Commission in a case argued on March 7 in the D.C. federal appeals court. And on and on.

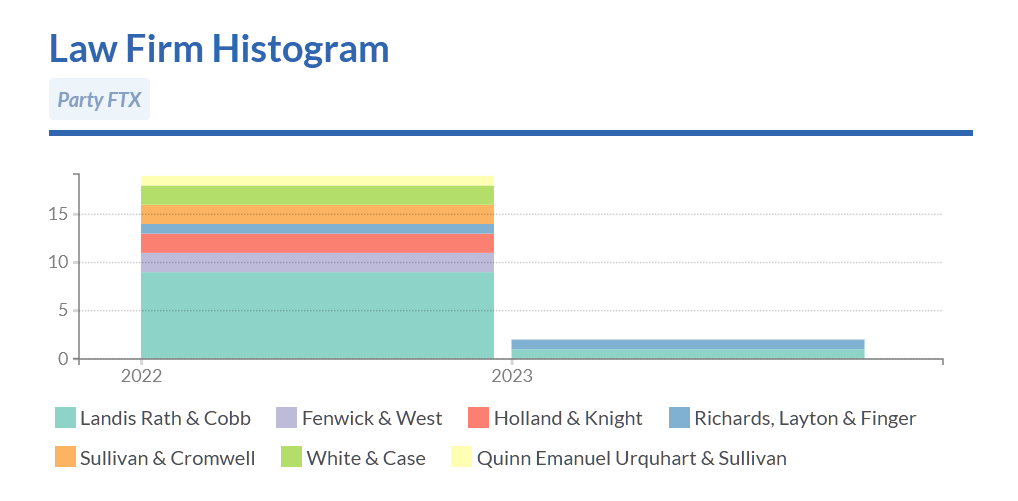

FTX and related entities have been sued dozens of times since the implosion. Thirty-one suits were filed against FTX entities in November 2022 alone. The cases are largely filed in Delaware bankruptcy court, but actions have been filed in state and federal courts nationwide.

FTX has been represented by a constellation of law firms, including Landis Rath & Cobb; Fenwick & West; Holland & Knight; Richards, Layton & Finger; Sullivan & Cromwell; White & Case; and Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan.

But if Freedom of Information Act requests to the SEC are any indication, few were asking about FTX before it cratered and the cryptoworld blew up.

More than 13 months before the world found out what a crook Bankman-Fried might be, Silverman, a freelance journalist, was nosing around. Silverman owns the distinction of being the first person to file a FOIA request with the SEC to find out what the agency knew about FTX.

FOIA requests to the federal government can be an important early warning of bad publicity, litigation to come, or, in the case of SBF and FTX, something much worse. PoliScio Analytics’ competitive-intelligence database FOIAengine tracks FOIA requests in as close to real-time as their availability allows. Of particular interest are news media requests, because investigations in progress can significantly affect stocks and markets once the stories hit.

According to FOIAengine, Silverman’s FOIA request was filed on September 30, 2021. Fittingly for this particular request, the SEC’s description of his request is cryptic: “FTX or FTX Trading Limited.” That’s it. And the agency’s response is equally terse: “Request Status: Closed. Agency Decision: Closed for Other Reasons.”

By then, questions were being raised about whether the SEC would regulate the roiling crypto marketplace. It would be another seven months – still, long before the crisis hit – before anyone else filed a FOIA request with the SEC about SBF or FTX. Notably, the second requester was, like Silverman, an independent journalist. The early requests about FTX and SBF didn’t come from established media outlets like the TV networks, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, or Bloomberg. Only after FTX shut down did those big players join the tidal wave of FOIA requests.

The SEC’s FOIA office sent back its official response 10 weeks later, on December 10, 2021. “We conducted a thorough search of the SEC’s various systems of records, but did not locate or identify any records responsive to your request,” a SEC FOIA research specialist told Silverman. No records about FTX. And nothing about Alameda Research, FTX’s conjoined cryptocurrency trading firm, which went bankrupt along with FTX.

“No records,” Silverman says now, “seems a little ridiculous.” The SEC’s press office did not respond to a request for comment.

By mid-June of last year, the S&P 500 fell into bear-market territory, and Silverman was still shadowing Bankman-Fried. June 13, the day the market buckled, was horrible not just for stocks but also for cryptocurrency, which by then had suffered a collective $2 trillion wipeout. Changpeng “CZ” Zhaoon, the CEO of Binance, the world’s biggest cryptocurrency exchange, tried to reassure customers. He tweeted that Binance was temporarily suspending Bitcoin withdrawals “due to a stuck transaction causing a backlog.”

Silverman tweeted slyly in response: “They have to find a volunteer, preferably someone small and lithe, to send in there and remove the clog. It takes time.”

Bankman-Fried, watching the exchange, didn’t see the humor. He tweeted back, directly to Silverman: “Likely just a technical issue.”

Coming next from FOIAengine: Elon Musk: Man, Myth, and FOIA.

John A. Jenkins, co-creator of FOIAengine, is a Washington journalist and publisher whose work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, GQ, and elsewhere. He is a four-time recipient of the American Bar Association’s Gavel Award Certificate of Merit for his legal reporting and analysis. His most recent book is The Partisan: The Life of William Rehnquist. Jenkins founded Law Street Media in 2013. Prior to that, he was President of CQ Press, the textbook and reference publishing enterprise of Congressional Quarterly. FOIAengine is a product of PoliScio Analytics (www.PoliScio.com), a new venture specializing in U.S. political and governmental research, co-founded by Jenkins and Washington lawyer Randy Miller. Learn more about FOIAengine here. To subscribe to FOIAengine, click here.

Write to John A. Jenkins at JJenkins@LawStreetMedia.com.